Carcasses attract deer, may spread chronic wasting disease

Block title

By: Kate StoneM.S. Avian Scientist

By: Kate StoneM.S. Avian ScientistMammals

We seek to understand the distribution and abundance of mammals. Several monitoring projects are underway.

Elk- Elk numbers fluctuate through the year with herds of several hundred animals moving onto the ranch in the fall and winter. Fewer elk stay around to raise their calves in the spring and summer. We track herd size, the habitat they use for feeding, and the amount of biomass available to them for forage. We are curious about how elk habits will change in response to changes in vegetation communities as restoration activities proceed.

Bears- The lower elevation draws and drainages at MPG were de-vegetated by herbicide applications and sheep and cattle browsing. As of the summer 2012, we have planted more than 30,000 trees and shrubs in these drainages. The plantings will provide cover for animals using the draw bottoms as travel corridors between the upland forests and the floodplain forests. Many of the shrubs we have planted, such as hawthorns, choke cherries, and serviceberry, will provide food for bears. Our bear monitoring efforts seek to document how many bears we have now and where they travel.

Click here for a link to a list of mammals we have seen and photos.

Click here for links to our best mammal footage.

We would like to do more small mammal research. Please contact us with ideas for collaboration. (Click here to contact us.)

In recent years, reports of chronic wasting disease (CWD) from several regions of Montana have hit the headlines. Now, Montana biologists are finding infected deer, elk, and moose in new areas, sparking regulations to limit the spread of the disease.

Chronic wasting disease affects the central nervous system of cervids, which are mammals within the deer family. Infected animals can lose weight and coordination and will eventually die. The disease is expected to be caused by prions, which are misfolded proteins. These prions concentrate in an animal’s central nervous system, although they can be found throughout its body. Animals may be exposed to the prions by direct contact with other animals or contact with feces, urine, saliva, blood, antler velvet, or carcass parts.

To limit the spread of CWD to new areas, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, has prohibited the transport of heads and spinal columns of cervids from Transport Restriction Zones. These regulations are critical because hunters often travel vast distances in Montana, moving carcass material far from the harvest site. In some cases, hunters illegally dump carcasses and butchering scraps on public lands or along rural roadways.

We have two ongoing scavenger studies that might help us understand how CWD spreads. In both studies, we watch carcasses and gut piles with game cameras. While viewing the photos, we have noticed that scavengers weren’t the only animals to visit carcass material–deer and elk visited too. The animals often lowered their noses to the gut piles and carcasses, although we are unsure how often they made contact. This carcass material could create a legacy of potential CWD exposure because prions can remain viable in the environment for years.

Deer and elk find gut piles and carcasses

The photos we explored came from two studies. First, we asked hunters to set up a game camera on a carcass or gut pile after killing an animal. Second, we placed game cameras on private properties to monitor carcasses associated with the Bitterroot Valley Winter Eagle Project. When examining camera footage, we counted the number of ungulates that investigated carcass material or stood on the bloody ground. We describe our methods at the end of this article.

Ungulates visited 16 out of 27 gut piles and carcasses (59.2%) left by hunters. Sometimes ungulates visited alone, while others visited in groups as large as 15 individuals. Visits lasted anywhere from less than 1 minute to more than 2.5 hours. In some cases, ungulates visited the site more than two weeks after the gut pile had disappeared.

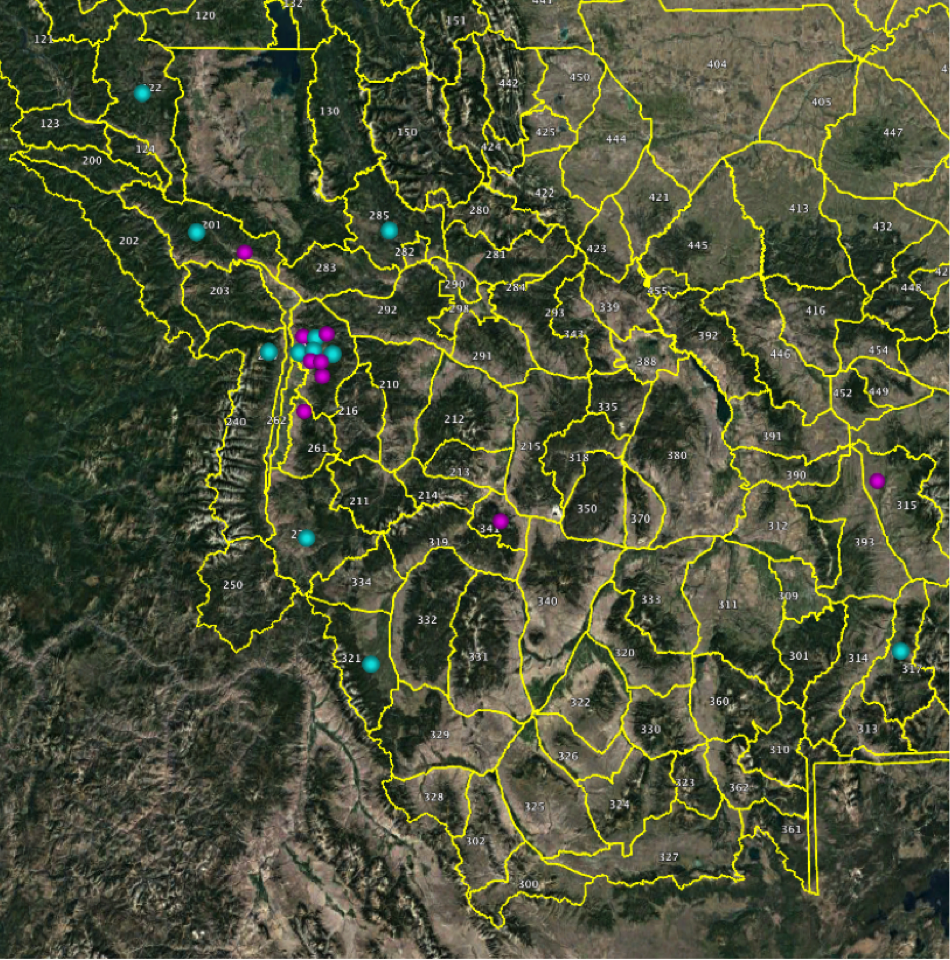

The map above shows the Montana hunting districts where ungulates did (blue) or did not (purple) visit carcass material left by hunters. To respect the privacy of the participants, we randomly placed points on the map within the hunting district in which the game camera was placed.

We recorded ungulates visiting all 28 sites associated with the Bitterroot Valley Eagle Project (map above). These locations span the width and length of the Bitterroot Valley, encompassing a range of plant communities and ungulate densities. At two sites, we left cameras through the winter and into summer, and both cameras documented ungulates investigating the area after we removed all signs of carcass material.

Recommendations to limit transmission of CWD

The primary sources of dead cervids include vehicle collisions and tissue left in the field by hunters. If we consider the Bitterroot Valley as a case study, the Montana Department of Transportation documented over 1000 dead cervids on highways in Ravalli County from January 2016 to 2020. Meanwhile, from 2016 to 2018, hunters killed an estimated 18,000 elk, mule deer, and white-tailed deer. We expect most hunters left some guts, bones, or butchering scraps in the field. Our images indicate that ungulates likely found much of this carcass material, and in areas where CWD occurs, this interaction may expose animals to prions.

Cervids visited some sites weeks or months after carcass material was scavenged or removed. This observation, combined with the persistence of prions in the environment, suggests that the potential for CWD exposure can be long-lived.

In CWD Management Zones, especially where cervid densities are high, management recommendations should encourage hunter behaviors that limit the contact of live and dead cervids. These behaviors could include removing all carcass material from the field after harvest, quickly collecting cervids killed on roads, and disposing of carcasses in an approved landfill.

The illegal disposal of harvested materials, like butchering scraps and bones, on public lands and along county roads is common in the Bitterroot Valley and elsewhere. That action concerns us because those carcass parts could have originated from an area where CWD occurs. We encourage hunters to adhere to regulations prohibiting the transport of carcass materials from CWD Management Zones and to dispose of carcasses in landfills. All hunters should consider these practices when possible because CWD can occur outside of CWD Management Zones.

Methods

We designed our studies to focus on scavengers, so we can’t make definite conclusions about how cervids behave around guts and bones.

The footage from hunters was recorded in 2018 and 2019 from Montana (n = 25) and Colorado (n = 2). We counted visits as separate if more than 30 minutes passed between detections or if species or individuals changed. We included multiple animals in one visit if ungulates were in a herd.

To study eagles and other scavenging species, we placed roadkilled deer and cameras on more than 30 private sites in the Bitterroot Valley during the winters of 2016-present. Sites occurred in river bottom forest, agricultural lands, foothill shrublands, and conifer forest. Of these sites, 28 of them had available footage.

This project has amassed over 800,000 pictures, and we use a public platform called Zooniverse that allows the public to help process imagery. We instruct volunteers to identify animals near the carcass and ignore animals in the background. We do not have a complete classification of all imagery, so we explored the roughly 10% of photos that have been classified. This dataset does not represent the complete processing of any year or site.

Acknowledgements

We thank the private landowners and hunters who participated in our game camera projects. We also thank the Montana Department of Transportation for their work collecting deer carcasses and providing data for this project.

About the AuthorKate Stone

Kate graduated from Middlebury College with a B.A. in Environmental Studies and Conservation Biology in 2000. She pursued a M.S. in Forestry at the University of Montana where her thesis focused on the habitat associations of snowshoe hares on U.S. National Forest land in Western Montana. After completing her M.S. degree in 2003, Kate alternated between various field biology jobs in the summer and writing for the U.S. Forest Service in the winter. Her fieldwork included projects on small mammal response to weed invasions, the response of bird communities to bark beetle outbreaks and targeted surveys for species of concern like the black-backed woodpecker and the Northern goshawk. Writing topics ranged from the ecology and management of western larch to the impacts of fuels reduction on riparian areas.

Kate coordinates bird-related research at the MPG Ranch. She is involved in both original research and facilitating the use of the Ranch as a study site for outside researchers. Additionally, Kate is the field trip coordinator and website manager for the Bitterroot Audubon Society. She also enjoys gardening and biking in her spare time.

Kate coordinates bird-related research at the MPG Ranch. She is involved in both original research and facilitating the use of the Ranch as a study site for outside researchers. Additionally, Kate is the field trip coordinator and website manager for the Bitterroot Audubon Society. She also enjoys gardening and biking in her spare time.